Flash (photography)

A flash is a device that produces an instantaneous flash of light (typically around 1/1000 of a second) at a Color temperature of about 5500K to help illuminate a scene. While flashes can be used for a variety of reasons (e.g. capturing quickly moving objects, creating a different temperature light than the ambient light) they are mostly used to illuminate scenes that do not have enough available light to adequately expose the photograph. The term flash can either refer to the flash of light itself, or the electronic flash unit which discharges the flash of light. The vast majority of flash units today are electronic, having evolved from single-use flash-bulbs and inflammable powders.

In lower-end commercial photography, flash units are commonly built directly into the camera, while higher-end cameras allows separate flash units to be mounted via a standardized accessory mount bracket. In professional studio photography, flashes often take the form of large, standalone units, or studio strobes, that are powered by special battery packs and synchronized with the camera from either a flash synchronization cable, radio transmitter, or are light-triggered, meaning that only one flash unit needs to be synchronized with the camera, which in turn triggers the other units.

Types of flashes

The earliest flashes consisted of a wad of magnesium powder that was ignited by hand.

All three of these devices used burning magnesium powder to provide the light for photography. This practice was widespread between the 1880s and the late 1920s, when the flashbulb was introduced. Each of these devices used different devices to ignite the powder. They are the Todd-Forrest magnesium flash lamp of 1907 (centre); the Agfa Blitz Lampe of 1910; and a flash lamp made from a First World War periscope which used a gunpowder cap to ignite the powder on the tray.

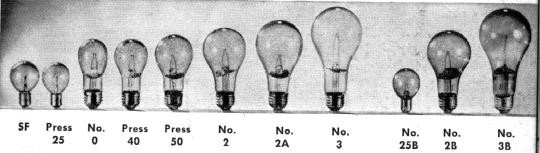

The first commercial flashbulb was patented in 1930. Previously, photographers used devices which burned magnesium powder to provide artificial light when required. The Sashalite bulbs were produced in the United Kingdom by the General Electric Company, and derived their name from a portrait photographer of the time known as ‘Sasha’, who was involved in their development.

Sashalite bulbs were the same size and had the same fitting as British electric light bulbs, and the instructions with them warned users not to fit the foil-filled bulbs in light sockets. Although the early flashbulbs were regarded as being safer than flash powders, they were prone to explode on occasions, showering the surroundings with glass.

Later, magnesium filaments were contained in flash bulbs, and electrically ignited by a contact in the camera shutter; such a bulb could only be used once, and was too hot to handle immediately after use, but the confinement of what would otherwise have amounted to a small explosion was an important advance.

For the Kodak Instamatic camera, flash cubes of 4 bulbs were introduced, that allowed taking 4 images in a row as the cube automatically rotated 90 degrees to a fresh bulb upon firing. The later Magicube was noteworthy in that each bulb was set off by a plastic pin striking a pyrotechnic element in the flash, so that a battery was not required.

Today's flash units are often electronic xenon flash lamps. An electronic flash contains a tube filled with xenon gas, where electricity of high voltage is discharged to generate an electrical arc that emits a short flash of light. (A typical duration of the light impulse is 1/1000 second.)

As of 2003, the majority of cameras targeted for consumer use have an electronic flash unit built in.

Another type of flash unit are microflashes, which are special, high-voltage flash units designed to discharge a flash of light with an exceptionally quick, sub-microsecond duration. These are commonly used by scientists or engineers for examining extremely fast moving objects or reactions, famous for producing images of bullets tearing through objects like light bulbs or balloons.

Technique

A flash is commonly used indoors as the main light source where there is not enough other light for a desired shutter speed. A fill flash is a low powered flash mixed with ambient light, and is often used to illuminate shadows on the side of a subject facing the camera. Another technique, bouncing a flash, involves pointing a flash upwards off of a surface, often a white ceiling, where it is reflected back onto the subject. Bouncing creates a more natural light effect and lessens shadows and glare but requires more flash power than a direct flash.

Part of the bounced light can be also aimed directly on the subject by "bounce cards" attached to the flash unit. That increases the efficiency of the flash and compensates shadows caused by light coming from the ceiling. It's also possible to use one's own palm for that purpose, resulting in warmer tones on the picture, as well as eliminating the need to carry additional accessories.

Flash Diffusers

Flash with diffuser provides more even light with

softer shadows than straight flash.

A diffuser can also reduce flash output to an acceptable level for close-up

macro work.

Note that diffusers reduce the usable flash range and can also alter white

balance, so you need to compensate as necessary.

Red-eye effect

The red-eye effect in photography is the common appearance of red eyes on photographs taken with a photographic flash when the flash is too close to the lens (as with most compact cameras).

The light of the flash occurs too fast for the iris of the eye to close the pupil. The flash light is focused by the lens of the eye onto the blood-rich retina at the back of the eye and the image of the illuminated retina is again focused by the lens of the eye back to the camera resulting in a red appearance of the eye on the photo. (This principle is used in the ophthalmoscope, a device designed to examine the retina.)

The effect is generally more pronounced in people with grey or blue eyes and in children. This is because pale irises have less melanin in them and so allow more light to pass through to the retina. Children, despite superficial appearances, do not have larger pupils but their pupils are more reactive to light and are able to open to the fullest extent in low light conditions. Many adults have lost the ability to fully open their pupils except through the use of drugs.

In many species the tapetum lucidum, a light-reflecting layer behind the retina that improves night vision, intensifies this effect. This leads to variations in the color of the reflected light from species to species. Cats, for example, display blue, yellow, pink, or green eyes in flash photographs.

Preventing red-eye

The red-eye effect can be prevented in a number of ways.

If direct flash must be used, a good rule of thumb is to separate the flash from the lens by 1/20 of the distance of the camera to the subject. For example, if the subject is 2 metres (6 feet) away, the flash head should be at least 10 cm (4 inches) away from the lens.

Professional photographers prefer to use ambient light or indirect flash as the red-eye reduction system does not always prevent red eyes, for example if people look away during the pre-flash. In any case, people with small pupils do not look natural on photographs. Many people also find the pre-flashes annoying. By coincidence, lighting that produces red-eye effect is also held to produce very unflattering photographs; hard and flat lighting is considered something to avoid.